What is the origin of virtual reality therapies?

Oculus Rift, Playstation VR, HTC Vive… You’ve probably come across one of these models in a store section. 3D glasses have become popular for entertainment purposes, but did you know that they also have a completely different utility? Hospitals and clinics now regularly use this tool to soothe patients who come to them. So how did this technology emerge in healthcare and what is its value? Let’s learn more about the history of therapeutic virtual reality with 3 key points: its beginnings, its development and its current use.

1. It all began in the 1990s with the aim of overcoming phobias

Virtual reality was not originally intended for the medical sector. In 1962, when Morton Heilig designed his Sensorama machine, the concept was based more on exploring the senses than on therapeutic work. Although the tool was later perfected to attract the space and military fields, it was not until the 1990s that its scope opened up to health.

So what was the first use of this immersive device? In 1995, researchers decided to exploit the possibilities of this innovative system to deal with patients’ anxieties. Indeed, an effective way to fight a phobia is to expose a person to his or her fear. In this way, the person gradually manages to tame his or her emotions and overcome them. However, gathering hairy spiders in a space or holding someone close to a precipice are difficult situations to set up. In contrast, virtual reality offers a safe setting to create them in a controlled and repeated way. The 3D environments, on top of being convincing, also work on phobias at a safe distance. In addition, the recreational aspect offers a more attractive approach than classical therapy.

With this point of view in mind, Daniel Mestre, research director at the Mediterranean Virtual Reality Centre, and his team have developed eight virtual environments to help acrophobic patients. Thus, they evolve in a house with a railing, a lift or in the middle of a canyon with a wooden bridge, depending on their state of progress. In the same vein, Hunter Hoffman, director of the University of Chicago’s virtual reality centre, designed the SpiderWorld virtual world to combat his patient’s arachnophobia. After 10 one-hour sessions, the success was resounding: she was able to hold a live tarantula in her hands.

These initial prospects open up a new field of experimentation. This technology is thus moving away from its entertaining or educational aspect to explore the area of care. As you can imagine, the history of therapeutic virtual reality does not end there. A few years later, research went even further.

2. Research that led to the first therapeutic virtual reality programme: SnowWorld

What if the immersion offered by virtual reality could reduce pain by diverting the subject’s attention? As a general rule, the more we think about our pain, the more it becomes the focus of our attention. It is one thing to know the fact, it is another to detach oneself from it. This is precisely where VR (virtual reality) headsets come in.

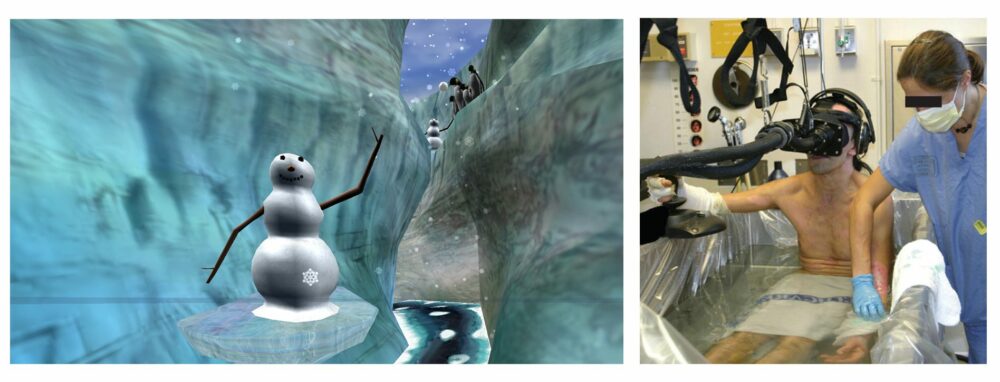

Photo credit: SnowWorld – University of Washington

Hunter Hoffman was a pioneer in testing this hypothesis. He first became interested in burn patients. Indeed, the care sessions take a nightmarish turn when the wounds have to be reopened for better treatment. To limit this suffering, the researcher has developed a virtual world specially designed to take away their pain: a snowy atmosphere with igloos, penguins and snowmen. The patient uses a joystick to walk through a canyon and throw snowballs. This frosty landscape is intended to counteract the burns experienced by the patient.

How can the effectiveness of this approach be assessed? To find out, Hunter Hoffman carried out MRIs (magnetic resonance imaging) with and without virtual reality goggles to compare the patients’ brain activity. The result? The activity of different regions involved in pain control and emotional management changes with the use of VR. Patients reported a 25 to 50% reduction in the intensity and unpleasantness of pain.

This success is all the more significant since the equipment used at the time was cumbersome and limited. However, the more realistic the immersion, the greater the reduction in pain. Today, technology has made it possible to perfect the device by offering a more immersive and realistic universe. Nonetheless, the principle remains the same: to mobilise the patient’s attentional resources so that he or she turns away from the pain signals.

Hardware advances are not the only change that has occurred since then. Indeed, the number of applications has multiplied. From dental care to surgical procedures such as transfusions, endoscopy or punctures, but also in delivery rooms, virtual glasses have conquered the medical sector and for good reason, as numerous studies attest to their analgesic and anxiolytic effect.

3. A therapy to combat anxiety and pain that has since been extended to other fields

Since the first work carried out by Hoffman and his team, the use of virtual reality has evolved rapidly and in some surprising cases. For example, Max Ortiz-Calan’s team has focused on chronic pain related to a phantom limb. The device consists of recording the activity of the remaining muscles of the amputated limb and then processing them using artificial intelligence. This data is then used to animate a virtual limb that can be seen and controlled by the patient.

After twelve sessions, the intensity and frequency of painful attacks were halved, as was their emergence during the night (-60%) and one of the volunteers even reduced his consumption of painkillers by 80%. These promising results will have to be confirmed with clinical trials, but it is difficult to deny the positive effect.

Along with the reduction of pain, the device is also accompanied by a reduction in anxiety. This last point has made it possible to diversify the action of therapeutic virtual reality and to intervene throughout the care process. Thanks to this effect, the device can be applied to all people subject to a stressful environment, such as carers.

Thus, virtual reality headsets contribute to facilitating clinical gestures, examinations and to bringing a sense of well-being in anxiety-provoking situations. Among the many applications, they can be used to:

- simplify PRP injections;

- reduce the time of surveillance after surgery;

- helping to perform an IVF puncture;

- manage the stress of a local anaesthetic;

- support the anxiety of palliative care patients;

- calming children in hospital;

- facilitating interventional radiology operations (biopsy, drainage, scanner, etc.);

- alleviate fears before a clinical examination such as a colonoscopy;

- favouring locoregional rather than general anaesthesia.

We could continue this list for a long time as this tool is applicable to so many cases.

The history of therapeutic virtual reality is still recent, but the evolution it has undergone demonstrates the potential of the device. Innovations tend towards better patient care, whether it be with lighter equipment, more refined simulations or additional techniques. For example, we use the benefits of music therapy, cardiac coherence and hypnosis to make our Healthy Mind solution even more effective.

Sources :

- Hoffman, H. G., Patterson, D. R., Seibel, E., Soltani, M., Jewett-Leahy, L., & Sharar, S. R. (2008). Virtual Reality Pain Control During Burn Wound Debridement in the Hydrotank. Clinical Journal of Pain, 24(4), 299‑304. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e318164d2cc.

- Hoffman, Seibel, Richards, Furness III, Patterson, Sharar, Virtual Reality Helmet Display Quality Influences the Magnitude of Virtual Reality Analgesia, The Journal of Pain, Vol 7, No 11 (November), 2006: pp 843-850.

- Hoffman, Richards, Bills, Oostrom, Magula, Seibel, Sharar, Using fMRI to Study the Neural Correlates of Virtual Reality Analgesia, 2006.

- Patterson, D. R., Wiechman, S. A., Jensen, M., & Sharar, S. R. (2006). Hypnosis Delivered Through Immersive Virtual Reality for Burn Pain: A Clinical Case Series. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis, 54(2), 130‑142. doi:10.1080/00207140500528182.

- Konstantatos, A. H., Angliss, M., Costello, V., Cleland, H., & Stafrace, S. (2009). Predicting the effectiveness of virtual reality relaxation on pain and anxiety when added to PCA morphine in 12 patients having burns dressings changes. Burns, 35(4), 491‑499. doi:10.1016/j.burns.2008.08.017.

- Max Ortiz-Catalan, Nichlas Sander, Morten B. Kristoffersen, Bo Hakansson, Rickard Branemark, Treatment of phantom limb pain (PLP) based on augmented reality and gaming controlled by myoelectric pattern recognition: a case study of a chronic PLP patient, 2014.

- Marion Jaccard, Mélanie Oliveira, Christophe Gueniat, Impact de l’hypnose et de la réalité virtuelle sur la douleur des grands brûlés lors de réfection de pansements, 2014.